As a specialist in presentations, I often find myself confronted by training participants who ask me how best to present in a project status meeting, or an information-sharing meeting, or some other kind of meeting.

They are initially surprised by my simple, blunt answer: “Don’t.”

Never pollute a meeting with an unnecessary presentation. A meeting is a great opportunity for discussion, interaction and decision-making. A presentation is an ineffective way of taking up valuable discussion time, or just lengthening a meeting and making it more boring than it should be.

Why is a presentation ineffective in a meeting situation? It’s very simple. We forget most of what we hear very quickly. This makes an oral presentation an extremely bad way of transmitting information from one brain to another. No matter that most presentations suck – even a TED-quality presentation is a very inefficient way of transmitting information.

Presentations are fantastic ways of transforming people, not informing them. If you want to change their beliefs, feelings or actions, by all means present. But if you want people to take in and remember new information, a far more effective way is to give them three things: a document to read; quiet time to read it; and coffee.

Here, therefore, are my five golden rules for meetings, and any company that follows these will most certainly cure their meeting overload problem, and free up time for real work.

1. Information is read, not presented

Amazon and LinkedIn are two of the world’s fastest-growing, most successful modern companies. One key point they have in common is that they do not allow presentations in meetings. (Neither did Steve Jobs.)

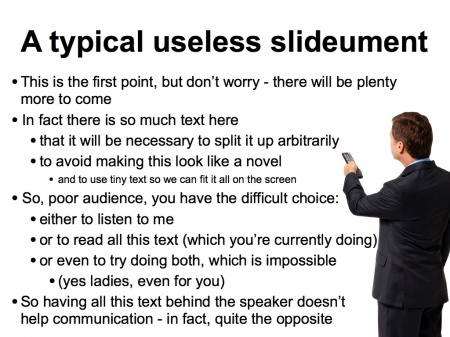

Instead, meetings begin with reading time. The meeting organiser has prepared and printed a real document – not a set of bullet-points, but a real standalone document with full paragraphs – and the meeting begins with at least ten minutes of silent reading time so that every participant is quite literally on the same page.

Of course, you can share the document in advance, but there’s always someone who doesn’t read it, so you need to leave them enough time in the meeting to read it. Everyone else can read it for a second time, and it’s worth doing.

This document contains all the context, background, details and ideas the participants need to know, as well as the meeting objective and the discussion points and decisions they aim to take. By reading it – ideally with a coffee – they will remember far more, and in far less time, than they would have if somebody had presented it to them orally. Then they can ask questions, discuss, and reach agreement in far less time than typical meetings take.

Forcing meeting organisers to prepare such documents – instead of their bullet-ridden slide decks – makes them think carefully about the meeting objective, and their subject. It also means that they only organise meetings they really need.

Lastly, this document is also very helpful for people who couldn’t make it or weren’t required to attend; and it makes writing up the meeting minutes so much faster.

Which brings me to point number 2:

2. Every meeting is minuted

If you’re going to take people’s valuable time, you need to have something to show for it. The initial document is a very helpful summary of the background. The meeting minutes should be annexed to this document, explaining the key points of the discussion, which decisions were taken, and which actions were agreed upon.

Providing the initial document and the meeting minutes to those who may need to be informed (even without participating) allows you to implement point 3:

3. No unnecessary participants

By always providing details of what happened in meetings, you can invite fewer people: busy managers will know that they will not miss out by not attending meetings, so it will no longer be necessary to invite people just so they stay informed about the topic.

The efficiency of any meeting is more or less inversely proportional to the number of participants: any more than six people, and productivity dives off a cliff. For some topics, two is a very good number; for others, three or four can be great. Five or six can sometimes work, but there is usually someone who participates very little in such a group.

Therefore it is vital to invite only those people who absolutely need to be there. Anyone else interested in the topic can elect to receive the brief and the minutes.

This frees up a lot of people, meaning on average everyone spends less of their day stuck in meetings. It also makes meetings more efficient, since conclusions can be reached faster with fewer participants. And this enables you to enact point 4:

4. Meetings last 25 minutes by default

In most companies, the default meeting duration is one hour. That’s how our calendars work, and nobody seems to challenge this idea. Yet it has two major problems.

The first is that an hour is a very long time to be sat in a meeting room, unable to get on with your real work, and many subjects don’t actually need that long.

The second is that if you have a 10.00-11.00 meeting in one room, and an 11.00-12.00 meeting on another floor or in another building, then you are almost certainly going to be late for the second meeting. If your day is full of meetings, you will create a domino effect. If people are routinely late for meetings, then people without prior meetings will also arrive late to avoid wasting time, and this thoroughly annoys those people who respectfully arrive on time.

Therefore I strongly recommend setting the default meeting duration to 25 minutes – including the ten minutes or so of quiet reading time at the start. Fifteen minutes can often be quite enough to make decisions when you already have all the background information, and when there aren’t ten or more people around the table.

Thus, if your meeting is from 10.00 to 10.25, and you have another meeting planned at 10.30, you still have five minutes to get to the next meeting, even with a short stop on the way if you have an important appointment with the smoking room, coffee machine or rest-room.

If 25 minutes just isn’t enough – and while it’s a good default, some meetings do need longer – then you can have meetings lasting 55 minutes. Always leave five minutes before the top or bottom of the hour so people can get to their next meeting on time. And always ensure that anyone requesting your time justifies why they need more than 25 minutes: this ensures they only request longer when it’s really necessary.

If your company always sticks to the default 25-minute duration, with the option of 55 minutes, then you will be able to enforce rule 5:

5. Meetings start and finish on time

In some countries, this may sound obvious: it’s a simple matter of respect that participants arrive on time and that the meeting organiser ensures they leave on time.

I live in France. It’s not obvious here. In fact, last week when I suggested this to a French client as a golden rule of meetings, I was bluntly reminded with a mix of shock and amusement: “But this is France!”

Yet this same client – and everyone else in the meeting – readily accepted that they find it very annoying and disrespectful for people to turn up late without an apology, and that it would be so much better if everyone was punctual.

The trouble with punctuality is that it is either a virtuous circle, or a vicious circle. If people are almost always on time, the exception stands out, and not in a good way. Latecomers feel bad, and will do their best not to be late again.

On the other hand, if lateness is tolerated, it becomes frequent, and even those who would prefer meetings to start on time may turn up late because they know for sure that there’s no point being on time. Thus a lack of punctuality becomes a vicious circle. If allowed to perpetuate, it becomes France. (And France is certainly not the least punctual place on the planet.)

Change needs to start at the top, so if senior managers make a point of always being on time, and calling people out for being late – and if you follow Rule 4, making it possible for people to be punctual – then you can build a culture where meetings regularly start on time.

Of course, they also have to finish on time, otherwise people will be late for their next meeting. Therefore the meeting organiser needs to take responsibility for timekeeping, and ensure that the meeting is summarised, decisions and actions are noted, and participants are free to leave, on time or ideally a little before.

Bonus Rule: No unnecessary meetings

It should go without saying – but I’ll say it anyway, because it isn’t that obvious in many companies – that you should only arrange meetings when you actually want people to participate and when you need something from them. Far too many meetings are just for information-sharing, and if you ask the organiser for his or her objective, it is simply: “So that people are informed about XYZ.” And naturally, they aim to present that information orally, perhaps with lots of bullet-points, giving participants hardly any chance of remembering X, let alone Y or Z.

As Garr Reynolds wrote, if the only reason for your presentation is to share information, you should distribute a handout and cancel the presentation.

Likewise, if the only reason for your meeting is to share information, cancel it, write the document, and share it. The reason people don’t do this any more is because nobody has any time to read such documents – because they spend so much of their time in meetings.

If you can cure their meeting overload, then you are giving them the gift of time, and they will have time to read such documents. Use a task manager to give them the task of reading your document so they get reminded of it; or find a spare ten minutes in their calendar and invite them to a meeting where they don’t have to go anywhere – they just have time blocked to read your document. This makes it far more likely they will read it than just sending them an email.

If you need a discussion, and to take decisions, and to establish an action plan, then a meeting can be useful. If not, it’s a huge waste of everyone’s time.

So let’s summarise these few golden rules of meetings:

- Information is read, not presented

- Every meeting is minuted

- No unnecessary participants

- Meetings last 25 minutes by default

- Meetings start and finish on time

And the bonus rule:

These simple rules are based on my long experience in major corporations, as well as the best practices of some of the world’s most dynamic organisations. I have absolutely no doubt that if you adopt these rules, your people will attend fewer meetings; the ones they do attend will not last as long, and will be more efficient; and that will boost your people’s productivity and pleasure at work. Maybe then your organisation will become as agile as Amazon or LinkedIn – but that’s up to you.

Try it, and please tell me how it works for you.

Posted by Phil Waknell

Posted by Phil Waknell

It’s now two years since

It’s now two years since

I am often asked about the flow of ideas in a presentation, and indeed it can be very hard to follow a presentation where the speaker moves from one idea to another without any transition, like a scatter-brained mother-in-law.

I am often asked about the flow of ideas in a presentation, and indeed it can be very hard to follow a presentation where the speaker moves from one idea to another without any transition, like a scatter-brained mother-in-law.